In the first of a series of 21 sonnets, Adrienne Rich introduces a new way of using the poem as a space for breaking silences with the power of language. Poem I of Twenty-One Love Poems defies the readers expectations of canon and lays the first stone down for intersectional participation in literature and the public sphere. Rich reframes women at the center of literature, and the delineation of structure and verse symbolizes their extrication. Thus in this piece, Rich uses deviations from classic sonnet form as well as juxtaposed imagery to carve out a distinct voice for queer women who exist in the city and its turmoil.

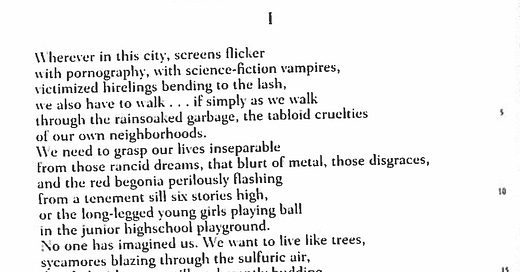

She veers from the sonnet to tell us that this is not a perfect piece about a perfect lover; instead it is a form of demystification and de-idealization for queer women. By using the tracking of an Italian sonnet, she is able to craft the workings of a love story in a new light. The work opens with reference to the objectification of women in daily life, eliciting images of “pornography” (2) and references to fictional and dramatized beings, and then moves to orient the reader to the self. The sonnet similarly moves down the body of a lover, this time the city, by looking above to the “screens” (1) and “sill six stories high” (10), and then moving away from these out of reach images down to where people “walk” (4), the “playground” (12), and how the subject is “rooted in the city” (16), thus grounding the reader back to reality, where humanity resides. They too are “inseparable” (7) from the harshness of the cityscape, and their love is slotted between a realm of softness and grime. To look away from the image of objectification used to describe women is where one can find an actual love for what women are.

Although in line with the sonnet, the prose does not utilize iambic pentameter nor rhyme scheme–it is written in free verse. The author is breaking away from a traditional representation of love and forming a new structure to how the love poem can be represented. The deviation from traditional themes is shown in the poem's length as well, extending the sonnet from the usual 14 lines to 16 lines. This extension mirrors resilience for the speaker and the addressee to continue on, and to expand past the boundaries created for them. By imagining anew the sonnet, the poet is rewriting the binary to include stories by women for women.

More explicitly, Rich targets the addressee of the poem in the statement “No one has imagined us” (13). This is the volta of the sonnet sequence, and it makes clear that the speaker and subject are one in the same, something that is not a part of societal or literary canon. With this, Rich is directly writing real women into canon and vying against heteronormative culture. Most romantic and petrarchan sonnets remain one sided or in the view of the speaker to the beloved. Here, a bridge is drawn between the speaker and the beloved, connecting them and instead posing them in relation to the outside world. Rich uses “us” and “our” versus the common “she” and “her” to make the point that the women of this poem are unified. Line 13 signals that they are deviating from the norm by making this a love poem that has never before been written. Although they are separate from the binary, they are present, and now make themselves known. To be inseparable from other mundane or base aspects of reality, is to be a part of it. In this poem perseverance is a form of love, to be a woman is to face inequality everyday and continue forward.

Unlike sonnet, which describes features that make the lover distinct, Rich represents love through its very existence. Rich encapsulates the feeling of resilience by drawing a comparison between the natural realm to that of the concrete city. By likening the lovers to the trees in the city, the imagery that springs forth is of growing and surviving in a milieu that opposes their very being. The sharp imagery of the “rain soaked garbage” (5) and the “blurt of metal” (8) force the reader to see the city for what it is– a hostile environment– and puts it in contrast to the “red begonia” (9) and the “sycamores blazing through the sulfuric air” (14) as beacons of an unbreakable collective. These glimpses of nature reside within the cityscape, they are not separate from it. The simile,“we want to live like trees” (15) conveys that lived experience shapes them. Trees, even damaged, grow tall and unwavering from the core of the bustling city. The red begonia is a symbol of hope, although a planted figure of beauty, it persits. Nature imagery parallels that of the woman in the public eye and its perseverance represents how queer women are integrated within society. There is not only contrast between the environment and the urban, but an innate human connection between the two that informs the rest of the work.

Thus leading to a vital point in Rich’s poem: the tie between society and the subject. This becomes apparent when the speaker says, “[w]e need to grasp our lives inseparable” (7). This modality brings to light Rich’s argument that women in literature must be demystified. The connection of women to their environment allows them to become all the more human. They “have to walk” through the “rancid dreams”, “disgraces”, and “tabloid cruelties of [their] own neighborhoods”(4-8). They are not put above the austere city, but rather grounded in it and grow from it nonetheless. This is a love story of a real person, not an ideal image. She iterates that the sycamores are “dappled with scars, still exuberantly budding” (15). The worst of their environment is a part of them, and they must operate under these systems and conditions of oppression. With Adrienne Rich’s background in activism, she is trying to represent an unlikely voice in the public sphere. Using the address of ‘We’ instead of ‘I’ or ‘You’, Rich speaks to the collective and evokes a transformative feeling to inspire a sort of global shift and call to action for minority communities to realize their strength. To love, itself, is a transformative experience. This story and the continuation of love cannot be told by omitting the struggles faced in the past and present, and the imagery of urban and environment inextricably intertwined with one another puts emphasis on this.

The final line of the poem furthers the actualization of queer women by once again focusing on the intrinsic quality of humans in their “animal passion” and expands on women’s ability to surpass boundaries while recognizing that they are “rooted in the city” (16). The reality of women's love for one another is that it is not something dainty or mythical, nor something to be objectified as perfect and pristine. Rich brings into focus the reality of being a lesbian and a woman in the modern world. Like trees they are resolute, and this likening translates over to a battle to speak up and secure their place in society. The real and raw quality of life for queer women comes across through the jarring imagery of the metropolis and natures place in it.

In this poem, The idea of the Woman is taken down from a pedestal and allowed to live in a truthful manner. By opening up the sonnet’s structure and rhetoric, Rich creates space for a new type of love story. To be alive, as a woman in love with a woman, centers them as human. The contrasting imagery allows the reader to empathize with this message, and the deviation from traditional structure expands on the point Rich is so vigorously making. This is poem 1 of 21, it sets the grounds for what is yet to come in her love story and paves the way for the presence of those not included in the current canon. By bringing the inseparable tie of women and society–and its issues–to the forefront of the poem, the speaker is representing what lesbian love is built of, and what it must face, to survive.

reading all 21 of these sonnets last fall was a real treat, and so I decided to take apart the first of many because it held so much in so little and really gave life to queer art and queer living in a modern space.